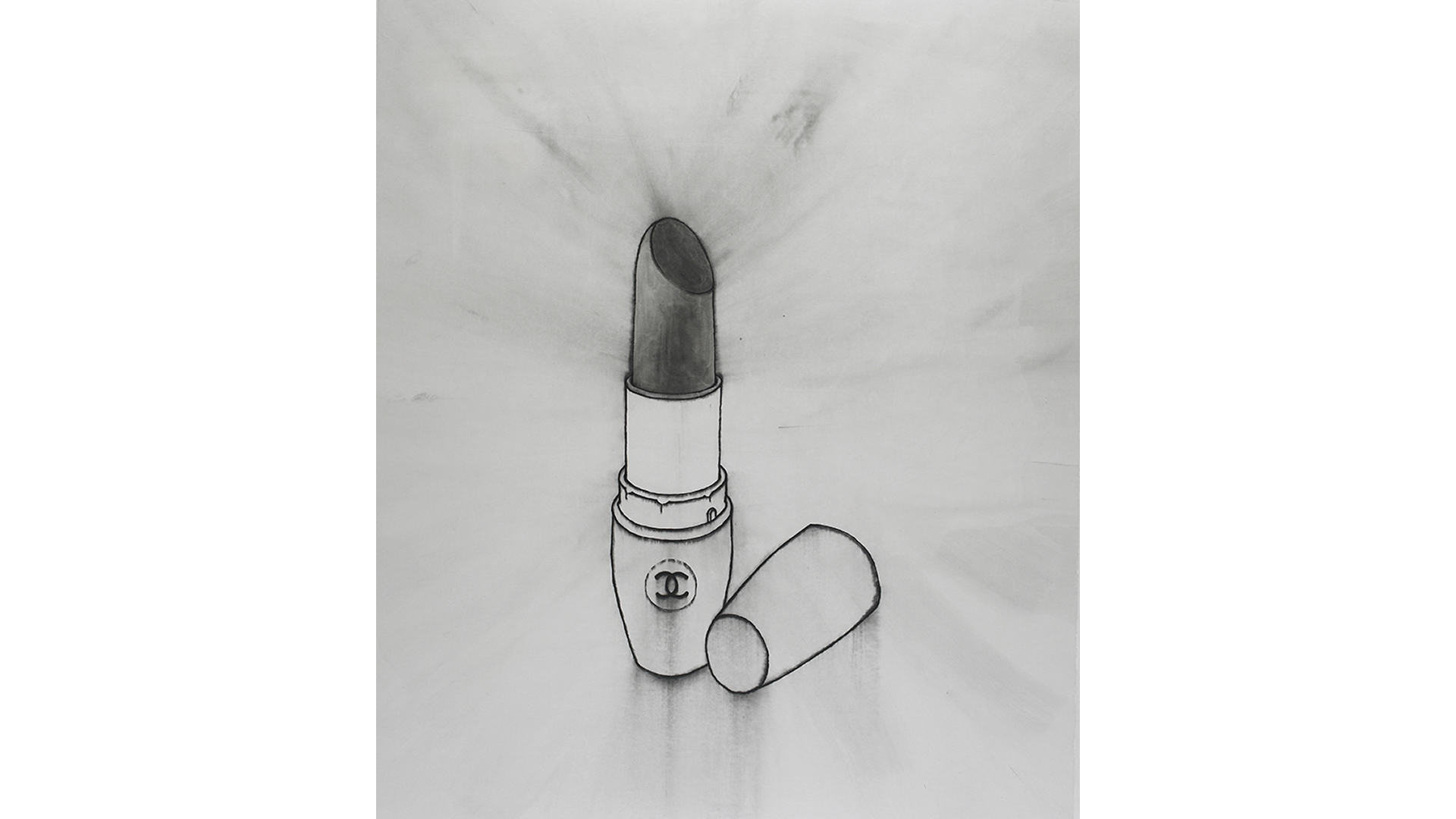

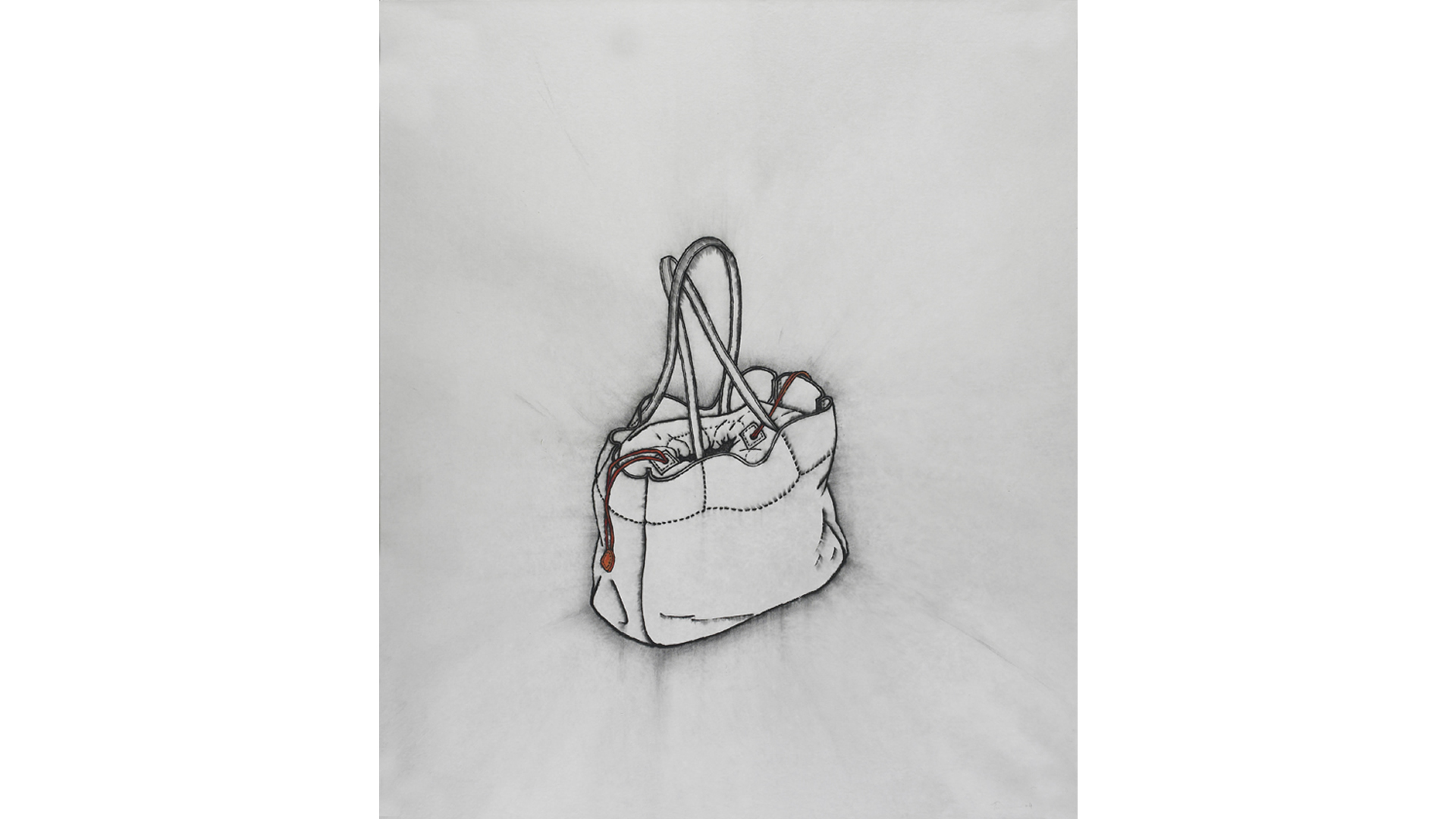

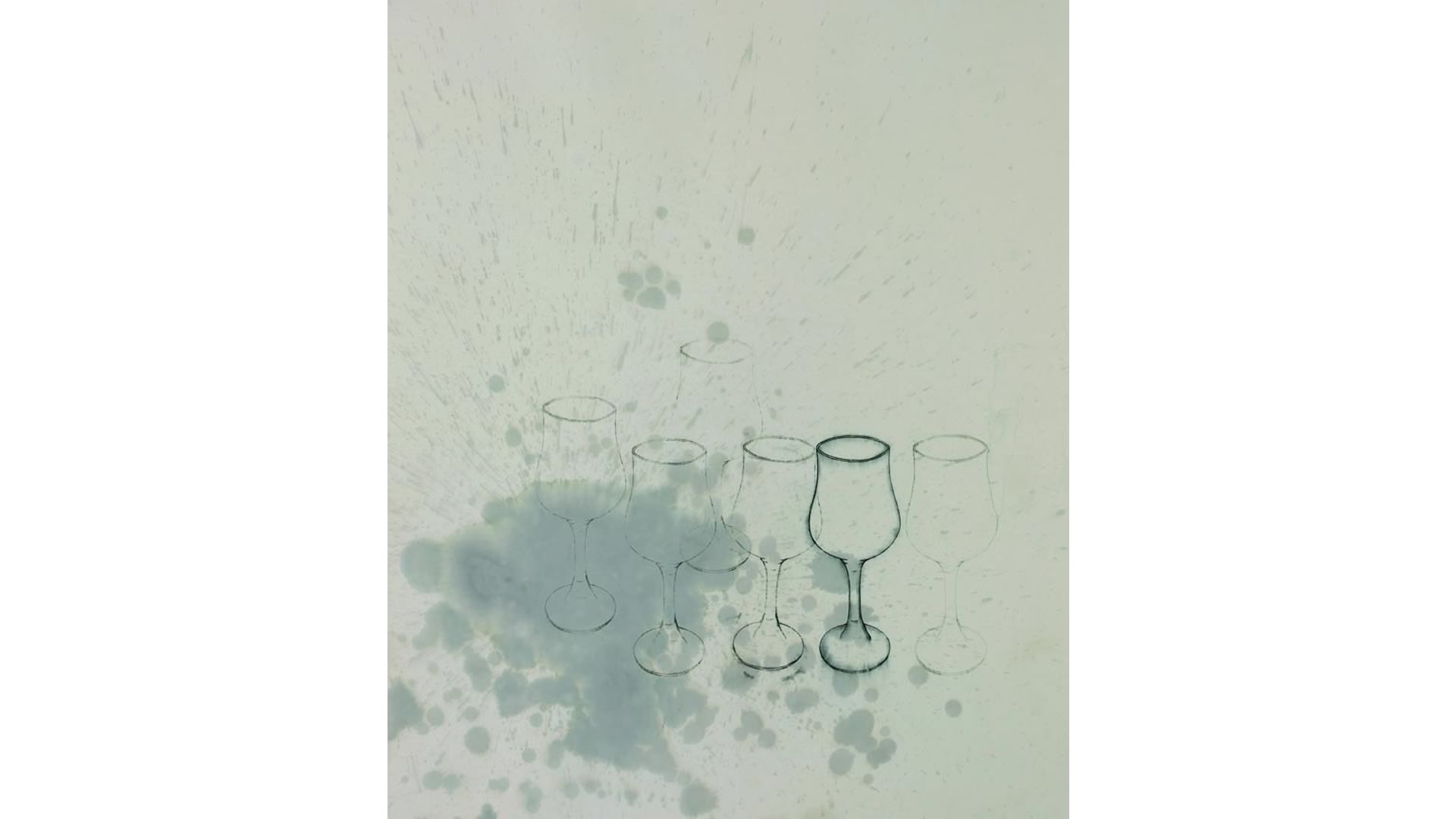

Sweet Bomb 2005-2007

The series of paintings depict objects like the lipstick, the handbag, the champagne glass, the jewellery or the perfume bottle; all of which are objects coveted by Chinese women henceforth trained for shopping and for consuming luxury products. In 1958 Mao warned the nation against the threat of capitalist temptations by introducing the concept of the “Sweet weapon”.

According to him, the bourgeoisie devoted itself to corrupt the people “by firing bullets wrapped in sugar” The fact that these dangerous objects are depicted by China ink, thus reintegrating the reality of the traditional support, proves that the artist learned in the meantime to make use of irony, a means of distancing, that enables her to occupy this space in-between cultures, that is to say the above-mentioned neutral ground.

The irony culminates in these circular compositions accompanied by other feminine utensils, tampons, absorbing objects in the same way as rice paper onto which they inscribe their “tadpole” movements. The round format recalls the microscopic view and favours the association with a spermatozoon.

The logic of Luo Mingjun’s trajectory is clear: it starts with the reinvention of the China ink technique and with the resort to calligraphy and to Taoist philosophy, passing through the gradual deconstruction of the text towards the appropriation of a personal imagery, to finally end up in an ironical critique of the tradition.